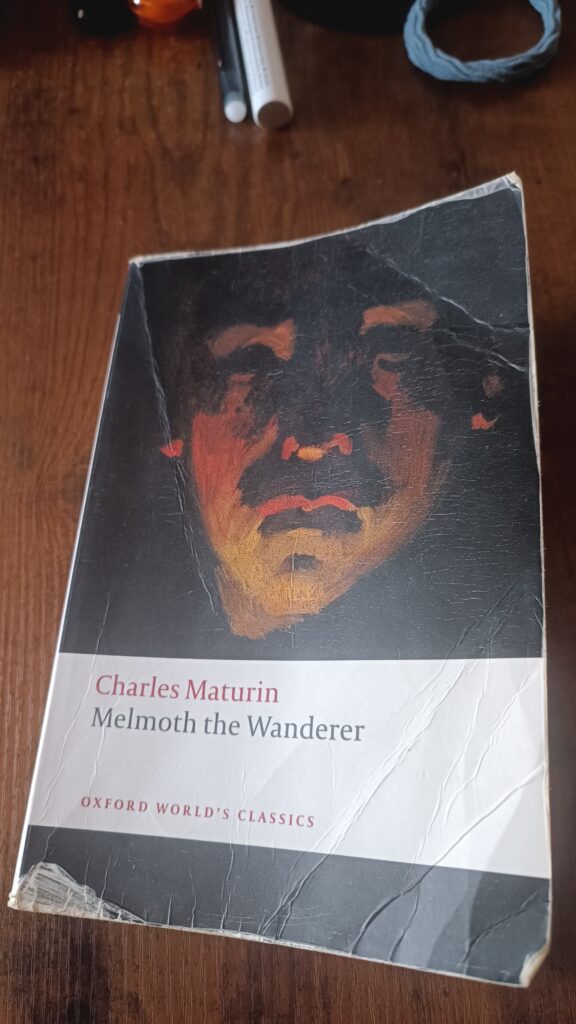

Written in 1820, this Gothic novel promises its readers unimaginable levels of dread in the depths of humanity.

We are in the middle of October, the days are getting darker and colder, and life has already slowed down a little. It’s time to settle in and enjoy our hot tea under a warm blanket. What else could be a better companion for this than a spooky book that sucks out the remaining spark of our already beaten-down morale?

Melancholy, at its finest. Despair, at its deepest. Dread, at its purest. As J. R. R. Tolkien once wrote, not all those who wander are lost. But some are, including Melmoth, who would do anything to show you the infinite cruelty this world offers the miserable folk… and shows a way out. But only for a while.

A Struggling Man and His Devotions

Charles Robert Maturin was an Irish novelist and clergyman who faced numerous challenges throughout his life. After an initial success writing under a pseudonym, he was compelled to reveal his true identity, which ultimately hindered his career in the clergy.

This contributed to his already tough financial situation, which was aggravated by his commitment to support his extended family, and Maturin eventually died in poverty. Forced to write to survive, he put all his struggles in his finest work, Melmoth the Wanderer.

A Nested Nightmare

A unique spin on the Faustian bargain, this book tells the tale of Melmoth, an Irishman who has already made a pact with the devil and is looking for someone to replace him. He is determined to save his soul from eternal damnation and is searching for pure-hearted people who are miserable enough to compromise their integrity.

The novel is framed by one story with several others nested within, like Matryoshka dolls, one more disturbing than the other, until we lose track of time, space, and characters. We’ll see how family, law, and organized religion can make or break people, to the point of insanity, heartbreak, and deep poverty. With pages filled with evil, sorrow, despair, wretchedness, and misery, a terrible fate is almost inevitable.

The Source of Evil

As a Protestant clergyman, Maturin was a passionate critic of the Catholic church and their often cruel practices, especially during the Spanish Inquisition, which we can observe in several parts of Melmoth the Wanderer. The religion of love, instead of helping the helpless, forces its way to power and destroys everyone who threatens its influence.

When we look further from the judgment on organized religion, we’ll be compelled to examine the occurrence of evil and its origin. Can temptation consume a pure-hearted, but severely tormented person to the point of selling their soul? Or those who do already have the seeds of evil within? As we’ll see, Melmoth’s victims are tormented by other people, who are motivated by selfishness, greed, religious fanaticism, and plain lack of mercy—and our antagonist simply offers them a way out.

The Burden of Reading

As heavy as it sounds, this book is worth reading. It does get confusing and messy, and I found so many details unnecessary. After all, we are talking about 500+ pages. But there are at least as many portions worthy of the commitment. Besides, sometimes misery gets interrupted by a glimpse of beauty, a bittersweet moment, a hope for justice. And why else would you read something like this, if not for the gripping tales? At least you’ll find out whether one of Melmoth’s victims took the bargain or not.

Here are some of my favorite quotes:

“A storm without doors is, after all, better than a storm within; without we have something to struggle with, within we have only to suffer; and the severest storm, by exciting the energy of its victim, gives at once a stimulus to action, and a solace to pride, which those must want who sit shuddering between rocking walls, and almost driven to wish they had only to suffer, not to fear.”

“In some circumstances, where the whole world is against us, we begin to take its part against ourselves, to avoid the withering sensation of being alone on our own side.”

“It is certain that the gloomiest prospect presents nothing so chilling as the aspect of human faces, in which we try in vain to trace one corresponding expression; and the sterility of nature itself is luxury compared to the sterility of human hearts, which communicate all the desolation they feel.”

“I loved, and to love is to live. Amid the disruption of every natural tie, —amid the loss of that delicious existence which seems a dream, and which still fills my dreams, and makes sleep a second existence, —I have thought of you—have dreamt of you—have loved you!”

“I love music, because when I hear it I think of you. I have ceased to love dancing, though I was at first intoxicated with it, because, when dancing, I have sometimes forgot you. When I listen to music, your image floats on every note, —I hear you in every sound. (…) Music seems to me like the voice of religion summoning to remember and worship the God of my heart.”

This post may contain sponsored or affiliate links.